Among the far-reaching effects of the pandemic, many of us have found ourselves taking a fresh look at things we previously took for granted. We may also see the return to our usual workplaces as an opportunity to ‘turn over a new leaf’, or be required by business needs to do things differently.

Those who have experienced significant shifts in work/home pressures may have new perspectives on inter-personal relationships. Their thoughts might be different now about accountability and the balance of how responsibility is shared.

A different lens

Similarly, those who have suffered bereavement or serious illness may now see the world through a different lens. It’s possible that their attitude to life, and behaviours stemming from it, will have changed accordingly.

We’ve certainly seen clients during the past year to whom these scenarios apply.

One manager who had lost a close family member to the coronavirus found that his usual toleration for a direct report’s emotional demands had evaporated. He was needing to re-set the boundaries. In another case, a significant business pivot required by the pandemic forced two executives to deal with their different approaches to decision-making. They decided to make a break with old habits and forge new ways of working – no doubt with implications for other colleagues.

These shifts can require adjustments for people managers and HR too. They may need to think again about team members and how they interact with each other, especially where a background of change presents fertile ground for tensions.

Thomas-Kilmann conflict model

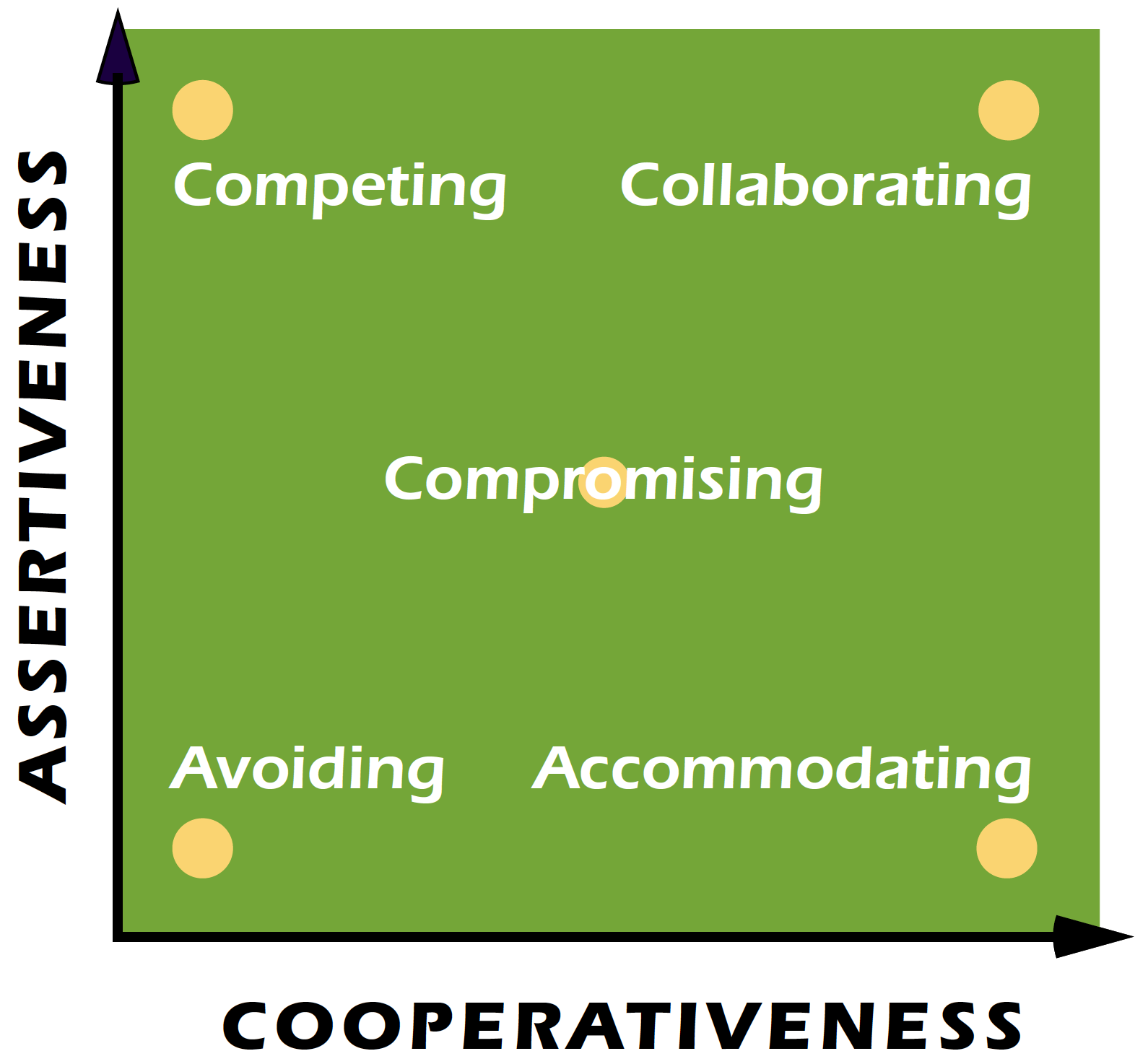

A useful way of understanding how people approach conflict is the Thomas-Kilmann model.

For those not familiar with the model, in brief, it suggests two axes of response to conflict:

- Assertiveness: where we seek to satisfy our own concerns.

- Cooperativeness: where we seek to satisfy the concerns of others.

We all use a mixture of those two approaches. The Thomas-Kilmann (T-K) matrix sets out the range of possible behaviours or conflict styles:

Which animal are you?…

Five animals have been used to represent the various conflict styles:

- The Accommodating Bear – sacrificing their own goal by giving way to others.

- The Avoiding Turtle – delaying or not dealing with the situation.

- The Compromising Fox – seeking the partially satisfactory middle ground.

- The Collaborating Owl – working to find a full, lasting solution with others.

- The Competing Shark – seeking to achieve their own goal at the cost of others’.

This short video provides a clear summary.

There’s no ‘right’ style. Each approach has its pros and cons depending on the circumstances. There are also a range of behaviours which fit each style and some are more constructive than others. For example, refusing point-blank to engage in a discussion about an issue is ‘turtle’-like behaviour. But so is a (more palatable) request to delay a conversation until everyone has had chance to think.

According to the model, our conflict styles depend on the inter-play of two concerns in a situation. How important it is that we achieve our goal vs how important it is to us to keep the relationship.

Thus, we can vary our style depending on what and who we’re dealing with. We could be a fox with a sibling and a turtle with an acquaintance. An owl with close work peers and a shark with someone we manage. However, we may be more adept at using one approach over another.

Using the model

Understand yourself and your team:

Whether team-building or addressing friction in a relationship, it is worth considering how people are likely to approach problems. Once you are familiar with the T-K matrix, what conflict style/s springs to mind for each person?

…but check out your assumptions:

Remember that some people’s experiences over the past 18 months may mean their past behaviour is an unreliable guide to how they will do things going forward. They may have been pushed further along one or other axis. In some cases, it may have resulted in a fundamental switch of their primary axis.

Introduce the model:

Consider introducing the T-K model to those involved. Our responses to conflict are often learned and habitual. But we can unlearn them – if we have insight about our dominant style and what other strategies are available to us.

…and encourage flexibility:

You could consider providing encouragement or coaching to key players to try alternative problem solving approaches that may better fit their aim in a situation. Or to adapt their dominant style to be more constructive. For instance, you can encourage a ‘shark’ to hear other ideas and explain why they feel they have the best answer rather than unilaterally imposing their way.

In those kinds of conversations, bear in mind the interplay (mentioned above) between achieving goals and keeping a relationship. It can be helpful to ask open questions to expose the cost/benefit of different approaches. For example: “What’s your goal in this situation and how important is it in context?”. “How important is this relationship to you (and/or to the team?)”. “How might you need to adapt your approach to achieve the best outcome for you/the other person/the team?”.

Consider workplace culture:

The T-K model also provides a way of looking at the broad workplace environment and how it might be influencing employees.

For example, is it realistic to encourage ‘bears’ to be more assertive in voicing or pursuing their ideas if they are either ignored or shot down in flames by a senior colleague? Will your efforts to encourage more ‘owlish’ collaboration in a team (which takes time and trust) be undermined by work overload or individualised targets?

The message is that we don’t work in a vacuum, and what is going on around us is a significant influence on our personal conflict styles.

So, as more staff return to newly challenging work environments, it’s useful to dust off this tried and trusted method for understanding our behaviour. The Thomas-Kilmann model gives you helpful insights for supporting teams and defusing frictions in support of a positive, constructive workplace.

If you would welcome talking through a conflict situation, between two colleagues or a team, to consider ways of handling it, feel free to contact us, without obligation.

More where this came from. Not subscribed to our regular blog on conflict at work? Please sign up here to receive our regular mailing.